Reversing the Course of Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Danyelle Sun and her family at the 2019 Annual SMA Conference. Courtesy of Danyelle Sun.

Danyelle Sun and her family at the 2019 Annual SMA Conference. Courtesy of Danyelle Sun.

Danyelle Sun’s daughter began walking when she was around 12 months old, but instead of growing ever more confident in her steps, she began to hesitate, falling more and more.

It took the better part of a year for doctors to identify the problem: spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). This progressive muscle wasting disease strips away mobility over time and in severe cases causes complete paralysis and even death in infancy. Sun’s daughter was diagnosed near age two, around the time the girl last walked. Sun noticed symptoms in her son at 10 months old, when he stopped pushing himself up with his legs to stand on her lap. For years, the young family was buffeted by lost abilities. “Every time you think you have a good handle on accommodations like the bathroom or their play area, they would lose another skill,” said Sun.

That pattern reversed itself after Sun’s kids began taking a new synthetic DNA drug called Spinraza (nusinersen) at ages six and three. Through regular injections, the drug is delivered directly into the cerebrospinal fluid to access the spinal cord and other nervous tissues.

Within months of the initial doses, Sun’s son regained trunk control and motor skills. “He was reaching out and giving me high-fives. I hadn’t seen that since he was nine months old,” said Sun. Her daughter, who started treatment at age six, gets less fatigued and can now independently use the restroom at school. “Anything that lets them do things like everyone else is a miracle,” says Sun. “We’d do anything for that.”

Spinraza was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2016. Over recent decades, there have been few new drugs for patients with nervous system disorders, but optimism is growing that a greater understanding of the genetics behind neurological diseases and improved gene-based technology will change that.

“A lot of the basic science that's needed to lead to new treatments and cures for neurological and psychiatric illnesses is paying off now.”Diane Lipscombe

director of the Carney Institute for Brain Science at Brown University and president of the Society for Neuroscience

“A lot of the basic science that’s needed to lead to new treatments and cures for neurological and psychiatric illnesses is paying off now,” said Diane Lipscombe, director of the Carney Institute for Brain Science at Brown University and president of the Society for Neuroscience.

Around 1 in 10,000 infants are born with SMA. The range of disability and life expectancy vary by genetics and access to care. Before Spinraza, no treatment stopped the inexorable loss of muscle strength in patients. Care options included walkers and wheelchairs, breathing machines, and spinal fusions to straighten a collapsing trunk. Research funding and patient advocacy efforts helped push the treatment into existence.

“Spinraza changed the entire course of history in SMA,” said Jill Jarecki, chief scientific officer of Cure SMA, a patient organization that has invested $75 million in research since 1984. That research included early studies on the unique genetics of SMA.

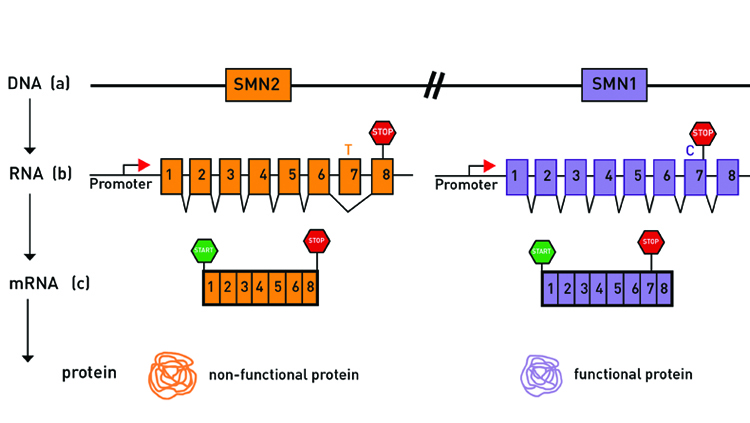

People with the disease are missing the gene that produces the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein, which is necessary for healthy motor neurons. But everyone, whether affected by SMA or not, has a near-perfect, mostly silent “backup” copy of that SMN gene. Some people have multiple copies. The broken gene copies produce a small amount of SMN protein. The more copies, the more backup SMN protein and the less severe the effects of the disease tend to be. In 2003, Cure SMA first funded researchers attempting to understand why the gene copies produced only a little SMN protein. It was not clear at the time that a treatment would emerge. “The funding of that science is a perfect illustration of how basic research can lead to therapy in ways that you may not anticipate,” said Jarecki.

Over the next decade, research on how to rouse the backup gene copies to produce more SMN protein would move from academic labs to biotechnology companies and into clinical trials. In tests with infants with SMA type I, half of the babies receiving the drug hit motor skill milestones such as head control and rolling over compared to none of the untreated babies. Older patients with SMA type II and III also saw improvements in trials.

The approval of Spinraza has been incredibly meaningful to patients, said Jarecki. Families now have options and more are expected. In May 2019, the FDA approved a gene therapy for SMA patients under two years of age. This single-dose treatment is delivered intravenously and provides a functional copy of the main SMN gene into patient nervous systems. Clinical researchers are also testing two oral drugs that can boost the activity of the ordinarily silent SMN copy genes. (One of the drugs was developed with funding from another patient group, the SMA Foundation.) Jarecki says in the future, patients may be able to combine therapies to optimize treatment depending on age and stage.