Inside Neuroscience: Scientific Strength Through Diverse Datasets

The generalizability of an experiment depends on how representative the data are — the accuracy of a particular animal model, or, for clinical studies, the diversity of the participants. Including people of different sexes, ethnicities, ages, and genotypes helps ensure that a study’s new finding is generalizable, or that a clinical trial’s treatment works for everybody.

But until recently, clinical studies disproportionately consisted of white men. Even studies in animal models included only male animals. The lack of inclusion, especially of traditionally underrepresented groups, is stark. This has had sweeping consequences: some biomarkers and genetic risk scores are only accurate for European people; life phases such as pregnancy and menopause are understudied; and treatments have inconsistent efficacy across races, body sizes, and other variables.

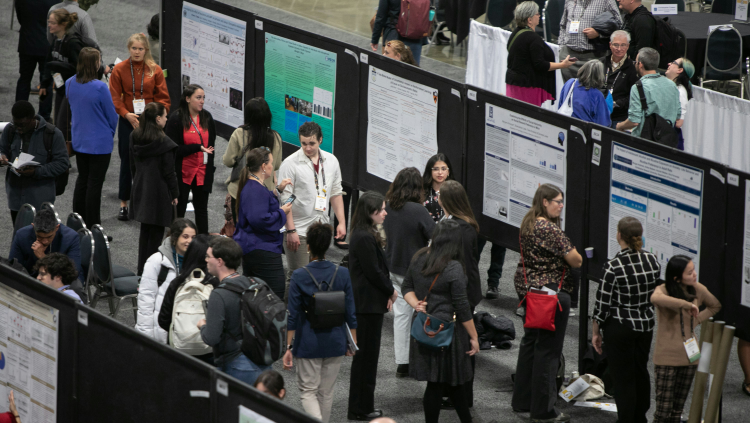

The biomedical research community at large, and neuroscientists in particular, are working to improve the diversity of their datasets. This effort will lead to new discoveries and more effective treatments, as well as a deeper understanding of how the nervous system can vary across individuals. Leaders of this shift shared updates on their work during a Neuroscience 2023 press conference titled “Scientific Strength Through Diverse Datasets.”

Damien Fair

“It could be argued that the driving factor of discovery and advancement of nearly every civilization has been the result of human variability,” said moderator Damien Fair, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Minnesota. “Importantly, at this crucial juncture in our history, there are many efforts to harness our privilege and awareness, to embrace our variability in both the data that we analyze and the people who are contributing.”

Sex as a Biological Variable

Men and women face different health risks and outcomes: over 80% of people living with an autoimmune disease are women, men and women differ in receiving diagnostic tests for strokes, and women are more likely to be misdiagnosed when they have a stroke.

But historically, women and female animals were excluded from research, and researchers defaulted to using only male animals to limit variability in their experiments.

Janine Austin

Clayton

“This lack of awareness around sex and gender consequences cascades within the health research space. And application of non-representative findings across different sexes and genders amplifies health inequalities,” said Janine Austin Clayton, director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

It wasn’t until the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 that the NIH required inclusion of women and minorities in NIH-funded clinical research. In 2016, the NIH instituted a landmark policy, the 21st Century Cures Act. The Act required the inclusion of female animals in pre-clinical research, that investigators account for sex as a biological variable, and that they justify scientifically single-sex studies. Today, over half of the participants in NIH-funded clinical research are women.

Including women and female animals does more than improve equity: it can increase rigor, too. Treating type 2 diabetes and high cholesterol can reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, but not for everyone. Researchers from the University of Arizona found that there are more women than men who don’t respond to the treatments and end up developing Alzheimer’s disease.

The Full Spectrum of Genetic Diversity

The University of Arizona group is also conducting a clinical trial testing if allopregnanolone can regenerate brain cells in Alzheimer’s disease. They have found no difference in the response between men and women, but people with a risk gene responded more than people without the gene.

Roberta Diaz Brinton

It’s important to break data analysis down by sex, genotype, and other variables in order to uncover how individuals uniquely develop the disease, said Roberta Diaz Brinton, professor of pharmacology and neurology at the University of Arizona. “What if the way that a person develops Alzheimer's disease is actually the road to therapeutic targeting for the off ramp for Alzheimer's disease?”

A study from Yale University examined how different autism subtypes are based upon unique differences in brain development. The group developed brain organoids using stem cells collected from autistic boys and their non-autistic fathers.

The organoids from the children displayed an imbalance in excitatory and inhibitory neurons compared to those from the fathers. But the direction of the imbalance varied based on the head size of the child: those with a larger head circumference had more excitatory neurons, while those with a typical head size had fewer excitatory neurons.

Flora Vaccarino

These results indicate that there are likely two biologically distinct subtypes of autism that may require different treatments. “Finding similarities and differences across individuals may inform not only our understanding of the development of those individuals, but also our understanding of brain disorders in a personalized fashion,” said Flora Vaccarino, a professor of neuroscience.

Following Socioeconomic Diversity

Sex differences are not the only variable driving individual variation. A longitudinal study called the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study is following some of these variables by tracking the development of nearly 12,000 children across the United States. Information about the children’s brain, cognitive, social, and emotional development as well as the environmental context in which they live is added to the database every year.

Nora Volkow

From the onset, it became clear that, on average, there were differences in brain development and cognition between children of different races and ethnicities, but these differences were driven by disparities in income and the social and structural environment, said Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Researchers have found that generally, children from lower income families had worse cognitive performance and smaller brain volumes compared to children from higher income families. However, when researchers examined the experiences of low-income children, they identified modifiable factors — such as greater financial assistance and other anti-poverty programs — that reduce these disparities. “Understanding these variables becomes crucial and highlights why we need to include in these studies diverse populations if we want to actually be able to address these problems,” Volkow said.

Journal Policies Support Diverse Data, Representation

Efforts to improve diversity have migrated outside the lab, too. The journal Nature has implemented policies to improve both the diversity of the datasets and the people doing the research.

Mary Elizabeth Sutherland

One policy encourages authors to include at least one researcher from the community being studied, such as making sure there is at least one woman author in a study on women’s health. The journal’s reporting summary asks submitting authors if they disaggregated their data based on sex, race, and ethnicity, and nudges them to explain why not if they didn’t. The journal hasn’t mandated anything yet, but it hopes to encourage scientists to think more about these different issues and be more intentional with their study design.

“Neuroscience is still far from representative,” said Mary Elizabeth Sutherland, a senior editor at Nature, but “there are so many great people who are really committed to making neuroscience something that improves and amplifies global voices, that improves health on many different levels, and makes us really understand all types of human beings and animals.”